This article is Version 2. Version 1 can be found here.

One of our main goals is to understand how socioeconomic quantities, such as gross domestic product, traffic congestion, patenting, crime, and others, scale with the size of the city. To do so, we need to understand what a “city” is, and this is much less straightforward than one might think.

An answer to that question is provided by the Italian physicist Cesare Marchetti (Marchetti (1994)), after whom Marchetti’s Constant is named. Titled Anthropological Invariants in Travel Behavior, Marchetti prepared the paper for the International Institute of Applied Systems Analysis. The paper’s central conclusion is that people typically spend about an hour per day travelling, or 30 minutes each way for a daily commute. Marchetti calls the rule an “invariant” because it has been observed in all societies from the Neolithic period to the present. A consequence is that transportation improvements may lead to a rebound effect, in that citizens will use the benefit to travel more rather than save travel time.

Marchetti justifies the word “anthropological” by arguing that the one hour of travel time is a basic instinct, transcending culture and ethnicity. It is based on a human instinct to balance the desire to control territory with the danger of exposure that comes with travel. Considering additional parameters of travel, Marchetti also finds that, in all times and cultures and across all levels of wealth, people typically spend about 13% of their disposable income on travel. He also observes that the death rate from automobile accidents is also an invariant–around 22 per 100,000 per year–regardless of the number of vehicles in circulation.

Origins of the Constant

Marchetti attributes his finding to a pair of reports by the transportation analyst Yacov Zahavi (Zahavi (1979) and Zahavi (1981)). An earlier formuation of the principle is found in Lewis Mumford’s Technics and Civilization (Mumford (1934)), Chapter 6, Section 2, which he in turns attributes to Bertrand Russell. Mumford asserts that with an improvement in transportation technology, people naturally spread their residences over a larger area, thus requiring the same travel time to reach a destination. Mumford argues that, by the same principle, improvements in communication technology, such as the typewriter and the telephone, have not resulted in any gain in efficiency because they have created a norm for greater volumes of communication with lesser value.

City Size and Mode of Travel

Prior to around 1800, most people did most of their traveling on foot. A typical walking speed is around 5 kilometers per hour, which enables a 2.5 kilometer travel radius with a travel time budget of one hour for a round trip. And indeed, Marchetti observes that most preindustrial villages have a radius of about 2.5 kilometers, or an area of around 20 square kilometers. Even the largest ancient cities, such as Rome, Persepolis, Marrakech, or Vienna, did not have city walls with a radius exceeding 2.5 kilometers.

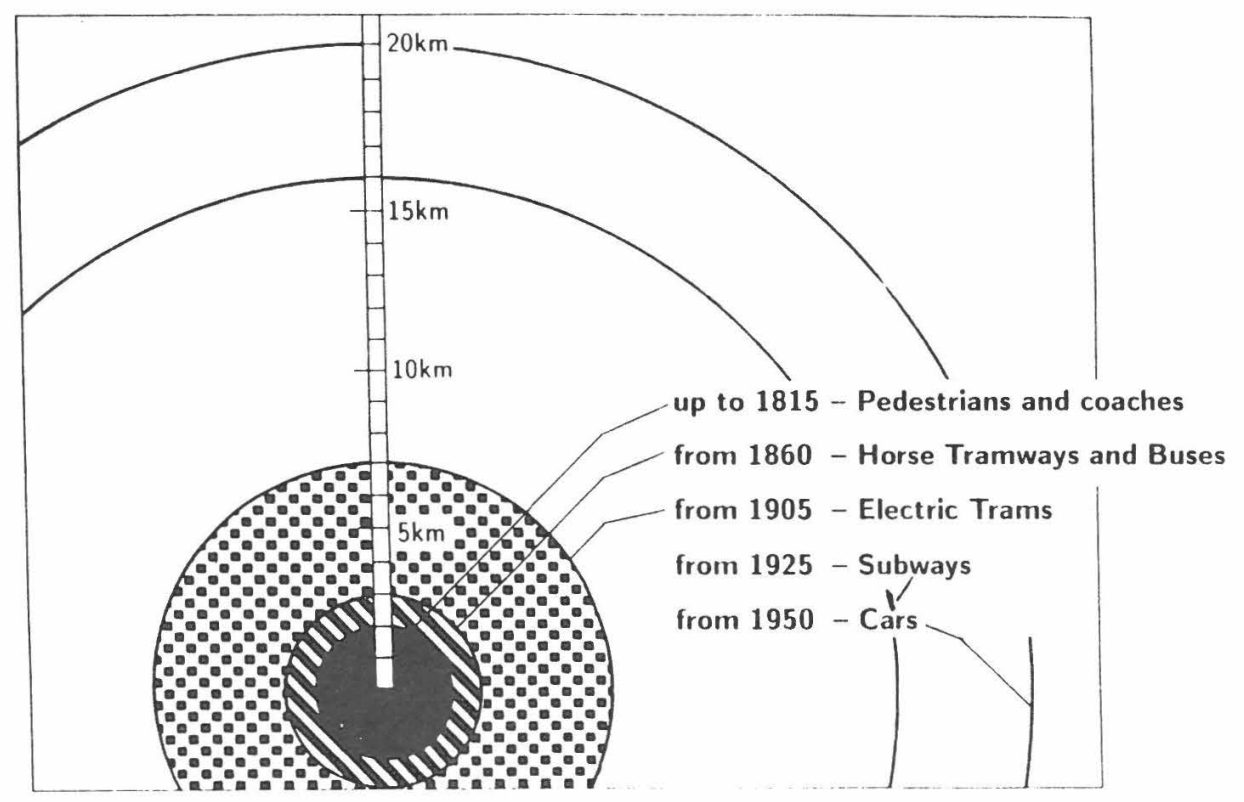

With the advent of faster modes of transportation that were widely available to the general public, the 30 minute commute radius expanded into a longer distance. Like many other cities at the time, Berlin in 1800 had a radius of 2.5 kilometers. In succession, horse tramways and buses, electric trams, subways, and private automobiles expanded the travel radius to 20 kilometers at the time of Marchetti’s research. An 8-fold increase in radius is equivalent to a 64-fold increase in the city’s area.

The growth of Berlin as transportation technology developed. Image from Marchetti (1994).

The growth of Berlin as transportation technology developed. Image from Marchetti (1994).

Marchetti posits that if a city grows in spatial extent while maintaining the population density of Hadrian’s Rome, then widespread automobile availability should enable cities of sizes of 50 million people, and a hypothetical means of transportation with a speed of 150 km/s should enable a city of a billion people. The issue of transportation infrastructure and population density is addressed elsewhere; skepticism of the assumption of constant population density with growing city spatial size is warranted.

Marchetti speculates about possible future transportation technology, such as hypersonic flight or a maglev train in tube evacuated to near-vacuum conditions, a concept similar to the more recent Hyperloop (Musk (2013)). Such technologies could enable what Constantinos Doxiadis termed an ecumenopolis, or a planet-spanning city (Doxiadis (1962)).

What About Communications?

Already by 1994, the dawn of the World Wide Web, there was widespread recognition of the importance of emerging communication technologies. And yet, Marchetti, citing Grübler (1989), regarded transportation and communication technologies as synergistic, not substitutes, and thus was skeptical of the idea that telecommunication alone could be a world unifying principle.

Research since 1994 has largely vindicated Marchetti’s skepticism. Hong and Thakuriah (2018) find that smartphone usage increases travel overall. Choo, Lee, and Mokhtarian (2007) find that telecommunications have a mixed effect on overall travel but generally increases travel. Choo and Mokhtarian (2007), Mokhtarian (2008), and Mokhtarian (2009) all show that physical transportation and telecommunications are generally complements: if one increases, then the other increases. Lyons and Urry (2005) find that mobile device usage stimulates travel by allowing travel time to be more productive.

Clark and Unwin (1981) find that communications technology increases travel overall, though it decreases work travel in rural areas and especially increases social travel. Salomon (1985) and Salomon (1986) show that communications increases travel on net.

Our analysis of remote work in particular suggests that an increased prevalence of remote work might increase the amount of nonwork travel, but it probably does not increase the amount of travel overall.

While modern communications technology changes the way we travel, and while we can imagine a world in which advanced telepresence is an adequate substitute for physical travel, there is little evidence that this is happening so far, and it is reasonable to suppose that physical transportation infrastructure will define the structure of cities for the foreseeable future.

Where are the Very Large Cities?

Marchetti considers not only the structure of individual cities, but also the relationships between cities. Zipf’s law (Zipf (1949)) is a well-known pattern whereby, when the populations of cities in a country are ranked, the nth value is proportional to 1/n. In other words, the second largest city has half the population of the largest city, the third largest city has a third the population of the largest city, and so on. Zipf’s law is a general pattern that has been observed in many domains besides city sizes.

Marchetti observes that there are few very large cities in the modern world, compared to what would be expected from Zipf’s law. To explain why, Marchetti observes that air travel creates corridors, often linear, such as Boston-New York-Washington, D.C. or Tokyo-Nagoya-Osaka. These corridors are too large geographically to function as unified labor markets for the general public, but fast air transportation integrates these cities economically for wealthy elites, which Marchetti suggests may be sufficient for these corridors to be functionally integrated. Marchetti then finds that when corridors are considered as functionally unified, Zipf’s law is found to much better fit world city size distribution.

Luckstead and Devadoss (2014) confirm the finding that there are fewer very large cities in the world than predicted by Zipf’s Law, based on statistical analysis of the 633 largest world cities and their populations in 2000, 2005, and 2010. The authors’ reason for this finding is, on a worldwide basis, there are restrictions to migration that do not allow the fullest rate of growth that might be achieved by the world’s largest cities. They predict that, in the future, restrictions to migration will continue to decline and the distribution of world city sizes will converge to that predicted by Zipf’s Law for the largest world cities.

Risks from Fast Transportation

The prospect of unifying world societies through fast transportation might not be perceived as an unalloyed good. Marchetti describes this as an ecological problem, by which he is referring not to environmental concerns but rather to a social cost of the loss of cultural diversity in the world, similar to how an environmental ecologist would wish to preserve species biodiversity. Since Marchetti (1994), perceived risk from cultural homogenization has been a concern with all forms of economic integration. For instance, Chu-Shore (2010) finds that free international trade in cultural goods, such as music and movies, leads to homogenization.

Marchetti argues that people have the natural inclination to return to their “caves”, regardless of where the day’s business might take them. Therefore, fast transportation will allow low-friction transactions between people around the world, yet it should preserve a geographically-rooted sense of home and thus cultural diversity.

The Size of Empires

Cities, roughly defined as a 30 minute commute radius, are not the only structures based on travel that Marchetti considers. He observes that ancient empires showed a maximum of one month of travel from the periphery to the capital; where travel times were longer than that, peripheral regions tended to split into separate political units. The geographic size was then determined by whether the predominant mode of transportation was by foot or by horseback. The advent of steamships and railroads, and especially of aviation, has at least enabled from a transportation logistics standpoint a world-spanning empire. The one month limit may again be a constraint on the size of functional political units in a spacefaring future.

The limit of an empire’s size, imposed by transportation logistics, is developed more fully in Marchetti and Ausubel (2013). Their work posits a maximum travel time of 14 days from the capital of an empire to the periphery, allowing a peripheral chieftan to travel to the capital, perform obeisance to the imperial ruler, and return home within a lunar cycle. Empires that exceed this travel time tend to be unstable and will fracture. The conclusion is supported by case studies of 20 historical and current empires.

Empirical Tests

Despite the purported universality of Marchetti’s Constant, obtaining the data required for empiprical tests is challenging. Dong et al. (2022) used smartphone location data to track commuting patterns for several cities in China, spanning two orders of magnitude in population. Despite the variance, the authors find the commuting distance to be a remarkably consistent 7.84 kilometers with a standard error of 0.0663 kilometers and no statistically significant relationship between size and commuting distance. The authors acknowledge the limitation that, while commuting distance is independent of city size, commuting time might grow with size, as larger cities tend to be more congested. The authors also acknowledge that their data only covers drivers and does not estimated commuting time or distance of mass transit.

Dong et al. (2022) conjecture that as cities grow, and an average commuting time into the city center greatly exceeds the 30 minute limit of Marchetti’s constant, cities tend to become more polycentric, meaning that they develop new employment subcenters.

Many readers may protest that their commuting time is significantly more or significantly less than the one hour posited by Marchetti (1994). Marchetti’s Constant is an average commuting in a society and not meant to be interpreted as a universal characteristic across all individuals. Mokhtarian and Chen (2004), considering several decades of survey results, found that average travel times varied significantly across socioeconomic gropus, including by gender, by age, by income, and other factors. Furthermore, travel time budgets were not constant within these groups. The authors conclude that the evidence does not support the idea of a fixed travel time budget.

Kung et al. (2014) use mobile phone and car GPS tracking data to identify commuting patterns in Ivory Coast, Portugal, Saudi Arabia, Boston, and Milan. They find that within each country or city, commuting times were independent of distance, offering supporting evidence for Marchetti’s constant. However, across different countries and cities, average commuting times differed, calling into question the idea that there is a single, universal travel time budget.

Yang et al. (2024) considered travel surveys covering Portland, Oregon in 1994 and in 2011. They found that the average weighted commute time increased from 22.8 minutes to 24.8 minutes over that period. Here, “weighted” means that the average is calculated for each mode of transportation, and the same weights are used in 1994 and 2011. Thus the increase in commute time reflects increase in commute time by individual modes and not mode shift.

Conclusion

Marchetti (1994) describes the fundamental principle of commute travel time for understanding the size of cities. The paper has some limitations. He may be off base with the constant density assumption to model cities with faster transportation infrastructure, and the discussion of the so-called ecological problem of high-speed transportation does not adequately address the issue. Still, the paper is valuable especially for integrating such a wide range of topics in a small amount of space, and doing so in a highly readable manner.

One implication of Marchetti’s work is that we should expect faster, cheaper, and safer transportation to manifest itself as more travel, rather than as saving time, money, and lives. This is not necessarily a bad thing, and it is an issue that is very familiar to people who understand the rebound effect in the context of energy markets. However, it calls into question the merit of strategies to address perceived negative impacts of transportation through better transportation infrastructure.

However, while there is strong evidence of an orientation to a 30 minute commute, the empirical evidence surveyed above suggests that this commute time is not a genuine constant. We may expect that transportation improvements will indeed reduce commute times, though perhaps not as much as would be expected from a naive calculation that ignores the rebound effect. Similarly, we may expect that increasing traffic congestion will in fact lengthen commute times.

References

Marchetti, C. “Anthropological Invariants in Travel Behavior”. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 47(1), pp. 75-88. September 1994.

Zahavi, Y., The “UMOT” Project, Project No. DOT-RSPA-DPB, 2-79-3, U.S. Department of Transport, Washington, DC, 1979.

Zahavi, Y., Beckmann, M. J., Golob, T. F. The UMOT-Urban Interactions, Report No. DOT-RSPA-DPB-10/7, U.S. Department of Transport, Washington, DC, 1981.

Musk, E. “Hyperloop Alpha”. August 2013.

Doxiadis, C. A. “Ecumenopolis: Toward a Universal City”. Ekistics 13(75), pp. 3-18. January 1962.

Grübler, A., “The Rise and Fall of Infrastructures”, Thesis, Physica Verlag, Heidelberg, Germany, 1989.

Hong, J., Thakuriah, P. V. “Examining the relationship between different urbanization settings, smartphone use to access the Internet and trip frequencies”. Journal of Transport Geography 69, pp. 11-18. 2018.

Choo, S., Lee, T., Mokhtarian, P. L. “Do Transportation and Communications Tend to Be Substitutes, Complements, or Neither? U.S. Consumer Expenditures Perspective, 1984-2002”. Transportation Research Record Journal of the Transportation Research Board 1, pp. 121-132. 2007.

Choo, S., Mokhtarian, P. “Telecommunications and travel demand and supply: Aggregate structural equation models for the US”. Transportation Research Part A-Policy and Practice, 41(1), pp. 4-18. January 2007.

Mokhtarian, P. “Telecommunications and Travel: The Case for Complementarity”. Journal of Industrial Ecology 6(2), pp. 43-57. February 2008.

Mokhtarian, P. “If telecommunication is such a good substitute for travel, why does congestion continue to get worse?”. The International Journal of Transportation Research 1(1), pp. 1-17. 2009.

Lyons, G., Urry, J. “Travel time use in the information age”. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 39(2-3), pp. 257-276. February-March 2005.

Clark, D., Unwin, K. I. “Telecommunications and travel: Potential impact in rural areas”. Regional Studies 15(1). February 1981.

Salomon, I. “Telecommunications and Travel: Substitution or Modified Mobility?”. Journal of Transport Economics and Policy 19(3), pp. 219-235. September 1985.

Salomon, I. “Telecommunications and travel relationships: a review”. Transportation Research Part A: General 20(3), pp. 223-238. May 1986.

Zipf, George K. “Human behavior and the principle of least effort”. Cambridge, (Mass.): Addison-Wesley, 1949, pp. 573.

Mumford, L. Technics and Civilization. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company. 1934.

Luckstead, J., Devadoss, S. “Do the world’s largest cities follow Zipf’s and Gibrat’s laws?”. Economics Letters 125(2), pp. 182-186. November 2014.

Marchetti, C., Ausubel, J. H. 2013. “Quantitative Dynamics of Human Empires”. Adapted from Marchetti and Ausubel, International Journal of Anthropology 27(1–2), pp. 1–62. 2012.

Chu-Shore, J. “Homogenization and specialization effects of international trade: are cultural goods exceptional?”. World Development 38(1), pp. 37-47. January 2010.

Dong, L., Santi, P., Liu, Y., Zheng, S., Ratti, C. “The universality in urban commuting across and within cities”. arXiv preprint arXiv:2204.12865. April 2022.

Mokhtarian, P.L., Chen, C. “TTB or not TTB, that is the question: a review and analysis of the empirical literature on travel time (and money) budgets”. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 38(9-10), pp. 643-675. November 2004.

Kung, K.S., Greco, K., Sobolevsky, S., Ratti, C. “Exploring universal patterns in human home-work commuting from mobile phone data”. PloS one 9(6): e96180. June 2014.

Yang, H., Lin, J., Shi, J., Ma, X. “Application of Historical Comprehensive Multimodal Transportation Data for Testing the Commuting Time Paradox: Evidence from the Portland, OR Region”. Applied Sciences 14(18): 8369. Septeber 2024.