Marchetti’s constant, discussed in greater detail on another page, indicates that the average person spends about an hour per day travelling. If this figure is taken precisely, it indicates that all improvements in transportation speed should manifest themselves as greater amounts of travel rather than saved time.

Induced and Latent Demand

Clifton and Moura (2017) distinguish between latent demand for transportation, which is demand that is desired but unrealized due to constraints, and induced demand, which is not currently consciously desired but would be stimulated from transportation improvements. Several studies, such as Parthasarathi, Levinson, and Karamalaputi (2003) and Næss, Nicolaisen, and Strand (2012), discussed in greater detail below, frequently use the terms ‘induced demand’ and ‘latent demand’ interchangeably, and they do not leave a clear indication as to which term is more appropriate.

Litman (2017) considers several mechanisms by which induced demand may occur from a road improvement. The improvement may divert traffic from other routes, either those that are less direct or those that are more direct but more congested. The improvement may divert traffic from other times of day into a time that for which the road was previously more congested. There may be a mode shift from walking, biking, or mass transit toward driving. The improvement may lead people to take longer trips, with or without a land use change such as developing homes or offices in a region farther from destinatons. The improvement may lead people to take trips that they otherwise would have not taken. Finally, Litman notes a cycle automobile-dependent land use that results from a high-capacity road system.

Rather than draw a binary distinction between latent and induced demand, Clifton and Moura (2017) present a hierarchy of six demands for transportation: realized travel (Level 1); scheduled travel (Level 2); tentative and planned travel (Level 3); aspirations and intentions (Level 4); dreams, desires, and possibilities (Level 5); and unimagined travel (Level 6). Each of Levels 2 through 6 can be regarded as a form of latent demand. The hierarchy does not distinguish between types of latent demand, such as taking more trips, taking farther trips, or taking a job farther from one’s home.

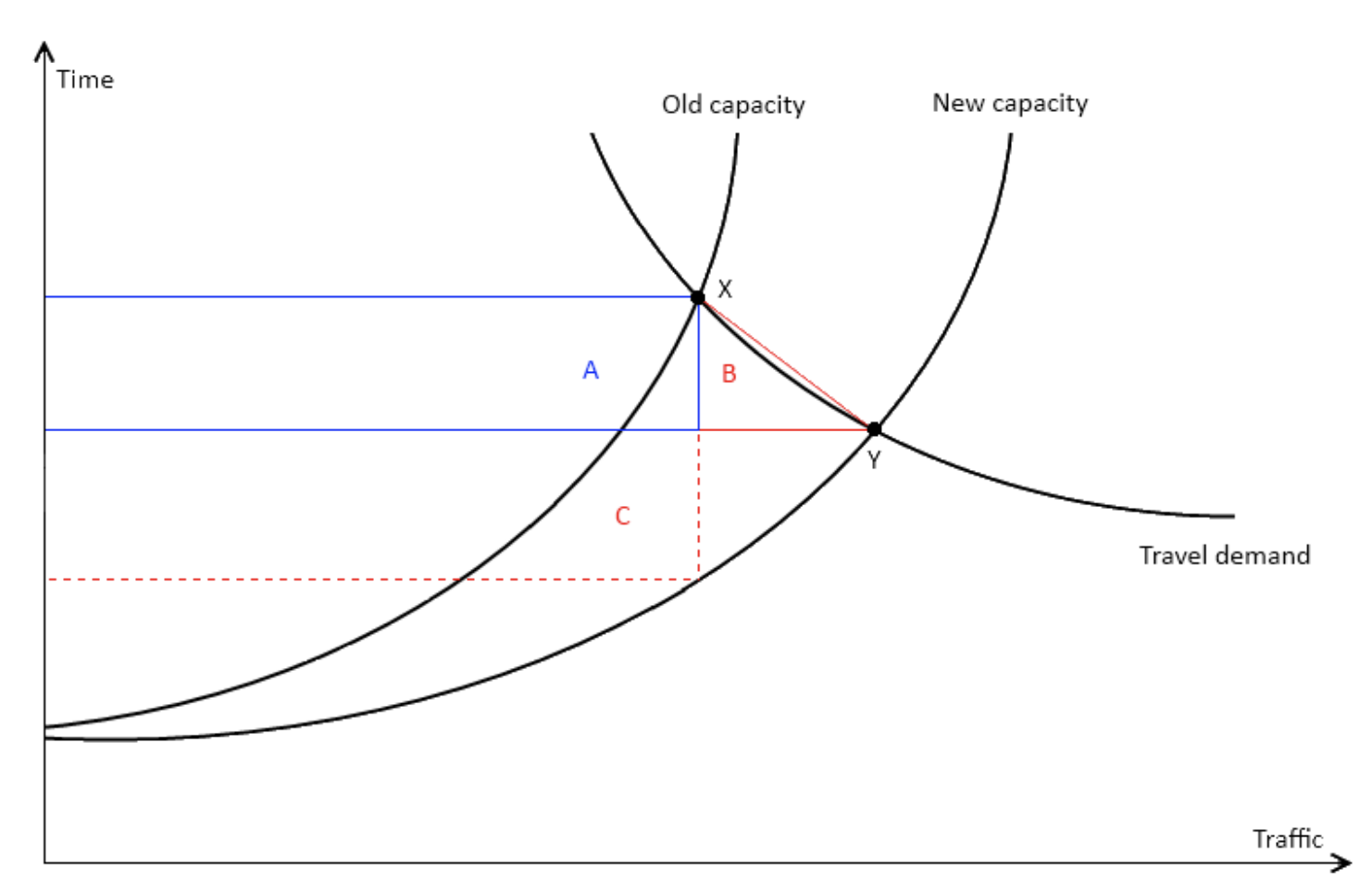

Image from Nielsen and Fosgerau (2005) via Næss, Nicolaisen, and Strand (2012)

Image from Nielsen and Fosgerau (2005) via Næss, Nicolaisen, and Strand (2012)

I prefer the term ‘rebound effect’ to describe this phenomenon for two reasons. First, I wish to avoid the difficulty of distinguishing between induced and latent effects, which can be quite difficult and is often handled sloppily in the literature. Second, I wish to analogize to the well-known rebound effect in energy economics. It is not clear to me that the distinction between latent and induced demand can cleanly be made, or that it is at all useful for transportation planning.

Rebound Effect

In energy economics, the rebound effect is the tendency for actual energy savings from an energy efficiency improvement to be less than expected from some energy efficiency innovation. Greening, Greene, Difligio (2000) document three types of rebound.

- Direct rebound is an increase in the demand for a good as a result of the lower price of the required energy. For example, LED lights are cheaper to operate than incandescent lights due to higher energy efficiency, and this may lead operators of LED lights to leave the lights on longer as a result.

- Indirect rebound is an increase in the demand for other goods resulting from energy efficiency in one good. For example, consumers may use the monetary savings that result from more fuel-efficient cars to take extra vacations by plane.

- Economy-wide rebound refers to price and quantity adjustments of various goods in the economy, with more energy-intensive industries seeing relative growth due to energy efficiency causing a fall in the real price of energy.

The rebound is defined as the portion of the expected savings that instead go to increased consumption via one of the above mechanisms. For example, a rebound of 0% means that all of the expected energy savings are achieved, while a rebound of 100% means that all of the expected savings go instead to increased consumption. Gillingham (2014) finds considerable variation in estimates of the magnitude of the rebound effect across studies, depending on location and the nature of the efficiency improvement. Studies also differ in how they define the three types of rebound and which they consider, with studies measuring direct rebound more common that those measuring indirect rebound, which in turn are more common than those measuring economy-wide rebound. As may be expected, studies that consider a broader range of rebound effects generally estimate higher rebound values.

Saunders (1992) advances what he calls the Khazzoom-Brookes Postulate and estimates that rebounds greater than 100%–meaning that energy efficiency leads to increased energy consumption overall–are common. Furthermore, Saunders finds that energy efficiency is an important mechanism behind long-term economic growth.

Rebound is not necessarily a negative thing, and discussion of rebound numbers below should not be taken as implicit condemnation of the various approaches, even though some cited studies come across as such. To judge the effect of rebound on cost-benefit calculus, it is necessary to know both the value of additional trips that the transportation improvement would bring as well as the external costs of those trips. It is not possible to estimate both of those things for the general case. Chan and Gillingham (2015) show, in the context of energy efficiency rebound, that the rebound effect is generally welfare enhancing, in that the value of increased energy consumption exceeds the negative externalities. If this is accepted, then while rebound may imply limitations in the ability of energy efficiency to achieve overall energy reduction targets, it is not a good argument against energy efficiency.

As a demonstration of the failure to account for these positive effects, Næss, Nicolaisen, and Strand (2012), estimate that perhaps 30% of the time-savings value of a proposed road expansion in Copenhagen would be lost to rebound, but they overestimate the loss by failing to account for a monetized benefit of increased travel.

Not all growth in travel can be reasonably attributed to the rebound effect.

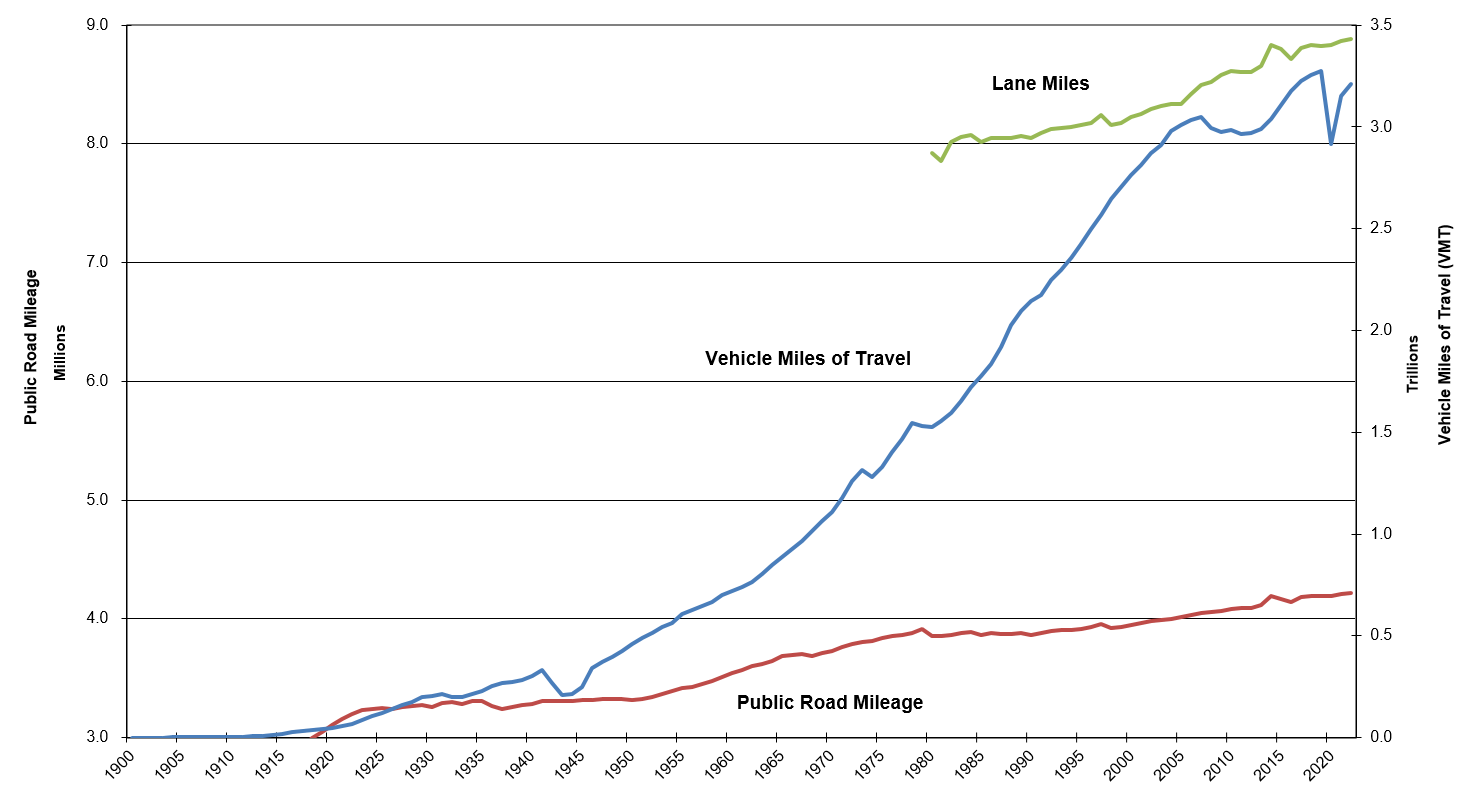

Image from the U.S. Federal Highway Administration.

Image from the U.S. Federal Highway Administration.

Data from the United States Federal Highway Administration indicates that from 1980 through 2022, public road mileage in the United States increased by 9% and lane-mileage by 12%, while total driving increased by 110%. A proper measure of the rebound effect would determine the increase in vehicle-kilometers traveled (VKT) attributable to the transportation improvement, which is generally different from the actual overall increase in VKT.

Rebound from Road Expansion

The existence of a rebound effect for adding new road lanes is well known. Some of the following studies are discussed in Litman (2017). Bear in mind that some of the following studies measure changes in vehicle-kilometers traveled (VKT) in terms of traffic speed, and some measure VKT in terms of lane-mile capacity of roadway.

Parthasarathi, Levinson, and Karamalaputi (2003), for instance, use data from road expansions in the Twin Cities Metropolitan Area from 1978 to 1998 and find that, of 12 models specifed, in 7 cases did an increase in the number of lanes increase the total number of VKT for a link. On interstsates and county highways, they found that a 1% increase in the number of lanes increased VKT by 0.553% and 0.067% respectively, while no statistically significant increase was found for trunk highways.

Næss, Nicolaisen, and Strand (2012) models a road expansion in Copenhagen. Their model finds that a 10% road capacity increase leads to a short-term traffic increase of 3-5% and a 10% increase within 15 years of the project being open. They find that a 5% increase of traffic reduces the time savings of the expansion by 40%, which in turn reduces overall benefits from the project by 30%. As noted above, the authors do not account for the value of additional throughput.

Cervero (2003) finds that a 1% increase in speed on California highways leads to a 0.637% increase in VKT. The figure is based on 24 highway expansion projects across the state from 1980 to 1994.

Graham, McCoy, and Stephens (2014) apply a generalized propensity score to observations from 101 cities and find that a 1% increase in lane-mileage increases VKT by 0.435% to 1.393%, depending on the scenario.

Hansen and Huang (1997) consider a panel set of observations for California highways from 1973 to 1990. They find that a 1% increase in lane-miles increases VKT to 0.6% to 0.7% in rural counties and by 0.9% in metropolitan counties.

Duranton and Turner (2011) analyze American interstates and sample data for 1983, 1993, and 2003. They find one of the higher estimates of elasticity that a 1% increase in lane-miles leads to an increase in VKT of 1.03%. The authors assess this figure to be the preferred estimate of several estimates derived from different statistical methods.

Hymel (2019) analyzes American highways in urban areas and find that a 1% increase in lane-miles roughly increases VKT by 1% over a five year period.

Fulton et al. (2000) consider cross-sectional time series data from Mid-Atlantic region in the United States: North Carolina, Virgina, Maryland, and Washington, D.C. and find that a 1% increase in lane-miles increases total VKT by 0.2% to 0.6%. The authors furthermore perform a Granger Causality test to confirm that the road improvements precede the increase in VKT.

Estimating rates of rebound from new road construction suffers from several methodological challenges, which may cause the estimates outlined above and in other papers to be biased upward. Dunkerley et al. (2018) find that many studies consider rebound on a single road, as opposed to expansion of an entire network. Since much of the induced traffic on an expanded road is drawn from other roads, the former approach will yield higher estimates of rebound than the latter approach. A second challenge of a literature review is publication bias; studies that find higher rates of rebound are more likely to be published, skewing upward the published values. Van der Loop, Haaijer, and Willigers (2016) observe that many studies fail to account for background growth in traffic and mistakenly attribute all increased traffic after a road expansion to that expansion, thus producing overestimates of the rebound effect.

Rebound from Remote Work

At first glance, one would expect an expansion in the rate of remote work to reduce traffic congestion and overall driving by removing some commuting trips. However, the rebound effect applies with remote work, in that at least some of the expected savings should be taken back in terms of more driving. As is the case with road expansion, the exact value of this rebound is debated. There are two main mechanisms by which rebound may occur: a remote worker may take more non-commute trips, and a remote worker may live farther from their place of employment.

Obeid et al. (2024) are among many researchers who have examined the first of these rebound mechanisms. Their work analyzes the rapid increase increase in remote working during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic and considers whether workers took more non-commute trips on days of remote working. They also find the number of additional non-commute trips in a week in terms of the number of days working remotely to counter the possible effect that these non-commute trips are merely shifted from other days rather than generated trips. They find, using both the daily and weekly analysis, that each day of remote work leads to approximate one additonal non-commute trip, suggesting that these are in fact generated trips rather than shifted trips. However, they find that generated non-commute trips are, on average, 15 kilometers shorter than the two-way daily commute, suggesting that despite the rebound effect, remote work does reduce overall driving.

The dataset employed by Obeid et al. (2024) contains months of observations for each individual, allowing for the model to account for fixed individual effects, fixed time effects, and individual effects that vary over time.

A limitation of Obeid et al. (2024) that may cause them to underestimate the rebound effect from remote work is that they do not account for the possibility of commutes themselves being longer as a result of access to remote work. The magnitude of this effect is hard to determine. While many studies find that people who work remotely on some days have longer commutes than those who do not, it is not clear that the option of remote work causes longer commutes; causation could very well go in the other direction, in that people who have longer commutes are more interested in remote work options.

To answer this question of causality, Zhu (2012) consider the change of commuting patterns over time. Using the National Household Travel Surveys, he finds that in 2001, remote workers had on average 34% longer commutes than non-remote workers, and this ratio has increased to 43% by 2009. However, the result of Zhu (2012) is less convincing in that it does not track the commuting patterns of individuals over time.

Rebound from Mass Transit

On a per-passenger basis, mass transit, such as buses and rail, saves urban space by up to a factor of 100, as estimated by Litman (2011). Therefore, an increase in the share of the population of a city that travels by mass transit might be expected to relieve congestion, and thus to produce a rebound effect in overall driving.

Beaudoin and Lawell (2018) consider a panel dataset of 96 urban areas across the United States from 1991 to 2011. The numbers vary widely across cities, but they find on average that a 10% increase in transit capacity leads to a 0.7% decrease in automobile travel in the short term, when only considering a substitution effect. However, in the long term and when considering substitution and induced demand effects, a 10% increase in transit capacity leads to a 0.4% increase in automobile travel. The magnitude of the rebound is found to be greater in larger and denser urban areas. Their analysis uses regional Federal transit as an instrumental variable, which is noted to correlate only loosely with actual congestion or transit need. Doing so should help mitigate the problem identified by Van der Loop, Haaijer, and Willigers (2016) of conflating induced demand with exogenous demand growth, though it is not clear how reliably.

Rebound from Mixed Use Development

Mixed use development refers to a development that is at a higher density than most developments and integrates residential, office, retail, and other types of facilities in a small area. Mixed use shortens the travel distance to many desired facilities, which should cause residents of mixed use neighborhoods to make more trips than those of more conventional neighborhoods.

Though the question of rebound from mixed use development is less well-studied than rebound from road construction, Sperry, Burris, and Dambaugh (2012) have considered this question. They conducted a travel survey of residents in a mixed use development in Dallas, Texas to determine which walking trips would have been conducted by other means if walking had not been an option. Aggregating results from their morning and evening surveys, they found that 46% of internal trips–trips whose origins and destinations are both within the development–and 16% of overall trips were induced and by foot.

We should not draw too strong a conclusion from a single study that is based on a single development, but Sperry, Burris, and Dambaugh (2012) do suggest, as theory would indicate, that rebound in transportation can derive from development patterns as well as from roads.

Conclusion

It is clear that rebound effects in transportation are widespread, and that some rebound in driving should be expected from road expansion, remote work, mass transit, and mixed use development. The precise magnitudes of the rebound in each case is difficult to estimate and surely varies considerably by context, though we suspect that the implication of Downs (1962) that transportation improvements are entirely unable to relieve congestion is greatly exaggerated.

The presence of widespread transportation rebound indicates how fundamental travel is to the functioning of a city. Chan and Gillingham (2015) show that the benefits of rebound for energy efficiency generally outweigh external costs. The impulse in urban planning to regard rebound, or induced demand, as a problem that needs to be curtailed is based on the assumption that this is not true with transportation. Indeed, we suspect that as Saunders (1992) shows with energy rebound, the expansion of mobility in a city is fundamental to the city’s prosperity.

References

Parthasarathi, P., Levinson, D.M., Karamalaputi, R. “Induced demand: a microscopic perspective”. Urban Studies 40(7), pp. 1335-1353. June 2003.

Næss, P., Nicolaisen, M.S., Strand, A. “Traffic forecasts ignoring induced demand: a shaky fundament for cost-benefit analyses”. European Journal of Transport and Infrastructure Research 12(3), pp. 291-309. 2012.

Nielsen, O.A., Fosgerau, M. (2005). Overvurderes tidsbenefit af vejprojekter? (in Danish). Paper presented at the conference Traffic Days at Aalborg University, Aalborg. August 2005.

Clifton, K.J., Moura, F. “Conceptual framework for understanding latent demand: Accounting for unrealized activities and travel”. Transportation Research Record 2668(1), pp. 78-83. 2017.

Litman, T. “Generated Traffic and Induced Travel: Implications for Transport Planning”. Victoria Transport Policy Institute. July 2017.

Cervero, R. “Road Expansion, Urban Growth, and Induced Travel: A Path Analysis”. Journal of the American Planning Association 69(2), pp. 145-162. 2003.

Graham, D.J., McCoy, E.J., Stephens, D.A. “Quantifying causal effects of road network capacity expansions on traffic volume and density via a mixed model propensity score estimator”. Journal of the American Statistical Association 109(508), pp. 1440-1449. October 2014.

Handy, S., Boarnet, M.G. “Impact of highway capacity and induced travel on passenger vehicle use and greenhouse gas emissions”. California Environmental Protection Agency, Air Resources Board, September 2014.

Hansen, M., Huang, Y. “Road supply and traffic in California urban areas”. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 31(3), pp. 205-218. May 1997.

Duranton, G., Turner, M.A. “The fundamental law of road congestion: Evidence from US cities”. American Economic Review 101(6), pp. 2616-2652. October 2011.

Hymel, K. “If you build it, they will drive: Measuring induced demand for vehicle travel in urban areas”. Transport policy 76, pp. 57-66. April 2019.

Dunkerley, F., Laird, J., Whittaker B., Daly, A. “Latest evidence on induced travel demand: An evidence review”. WSP, Rand Europe. May 2018.

Van der Loop, H., Haaijer, R., Willigers, J. “New findings in the Netherlands about induced demand and the benefits of new road infrastructure”. Transportation Research Procedia 13, pp. 72-80. January 2016.

Fulton, L. M., Noland, R. B., Meszler, D. J., Thomas, J. V. “A Statistical Analysis of Induced Travel Effects in the U.S. Mid-Atlantic Region”. Journal of Transportation and Statistics. April 2000.

Sperry, B.R., Burris, M.W., Dumbaugh, E. “A case study of induced trips at mixed-use developments”. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design 39(4), pp. 698-712. August 2012.

United States Federal Highway Administraton. “Highway Statistics Series”. Accessed November 19, 2024.

Greening, L. A., Greene. D. L., Difligio, C. “Energy efficiency and consumption — the rebound effect — a survey”. Energy Policy 28(6-7), pp. 389-401. June 2000.

Gillingham, K. “Rebound Effects”. Prepared for the New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics. November 2014.

Saunders, H. “The Khazzoom-Brookes Postulate and Neoclassical Growth”. The Energy Journal 13(4). October 1992.

Chan, N.W., Gillingham, K. “The microeconomic theory of the rebound effect and its welfare implications”. Journal of the Association of Environmental and Resource Economists 2(1), pp. 133-159. March 2015.

Litman, T. “Smart congestion reductions II: Reevaluating the role of public transit for improving urban transportation”. Victoria Transport Policy Institute. January 2011.

Beaudoin, J., Lawell, C.Y. “The effects of public transit supply on the demand for automobile travel”. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management. 2018 Mar 1;88:447-67.

Obeid, H., Anderson, M.L., Bouzaghrane, M.A., Walker, J. “Does telecommuting reduce trip-making? Evidence from a US panel during the COVID-19 pandemic”. Transportation research part A: policy and practice 180:103972. February 2024.

Zhu, P. “Are telecommuting and personal travel complements or substitutes?” The Annals of Regional Science 48(2), pp. 619-639. April 2012.

Downs A. “The law of peak-hour expressway congestion”. Traffic Quarterly 16(3). July 1962.