One of our main goals is to understand how socioeconomic quantities, such as gross domestic product, traffic congestion, patenting, crime, and others, scale with the size of the city. To do so, we need to understand what a “city” is, and this is much less straightforward than one might think.

An answer to that question is provided by the Italian physicist Cesare Marchetti (Marchetti (1994)), after whom Marchetti’s Constant is named. Titled Anthropological Invariants in Travel Behavior, Marchetti prepared the paper for the International Institute of Applied Systems Analysis. The paper’s central conclusion, which Marchetti attributes to the transportation analysist Yacov Zahavi (Zahavi (1979) and Zahavi (1981)), is that people typically spend about an hour per day travelling, or 30 minutes each way for a daily commute. Marchetti calls the rule an “invariant” because it has been observed in all societies from the Neolithic period to the present.

Marchetti justifies the word “anthropological” by arguing that the one hour of travel time is a basic instinct, transcending culture and ethnicity. It is based on a human instinct to balance the desire to control territory with the danger of exposure that comes with travel. Considering additional parameters of travel, Marchetti also finds that, in all times and cultures and across all levels of wealth, people typically spend about 13% of their disposable income on travel. He also observes that the death rate from automobile accidents is also an invariant–around 22 per 100,000 per year–regardless of the number of vehicles in circulation.

City Size and Mode of Travel

Prior to around 1800, most people did most of their traveling on foot. A typical walking speed is around 5 kilometers per hour, which enables a 2.5 kilometer travel radius with a travel time budget of one hour for a round trip. And indeed, Marchetti observes that most preindustrial villages have a radius of about 2.5 kilometers, or an area of around 20 square kilometers. Even the largest ancient cities, such as Rome, Persepolis, Marrakech, or Vienna, did not have city walls with a radius exceeding 2.5 kilometers.

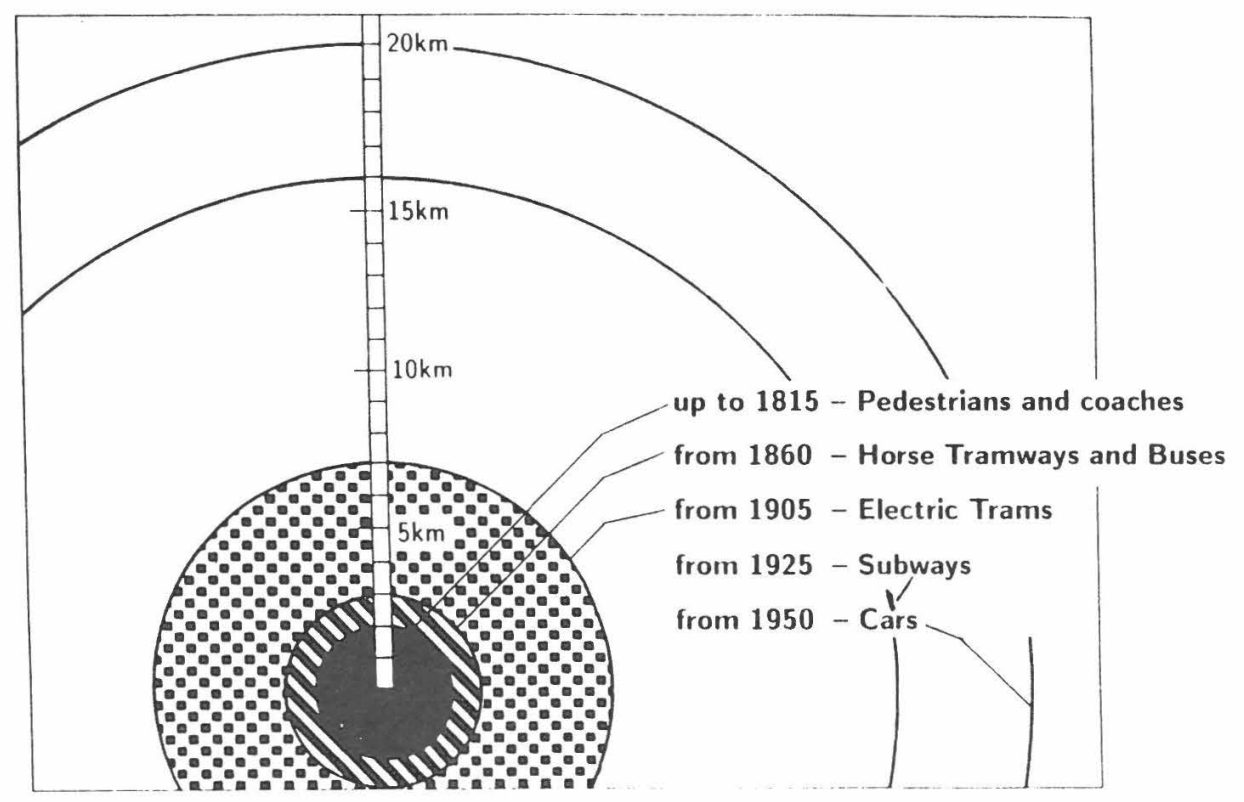

With the advent of faster modes of transportation that were widely available to the general public, the 30 minute commute radius expanded into a longer distance. Like many other cities at the time, Berlin in 1800 had a radius of 2.5 kilometers. In succession, horse tramways and buses, electric trams, subways, and private automobiles expanded the travel radius to 20 kilometers at the time of Marchetti’s research. An 8-fold increase in radius is equivalent to a 64-fold increase in the city’s area.

The growth of Berlin as transportation technology developed. Image from Marchetti (1994).

The growth of Berlin as transportation technology developed. Image from Marchetti (1994).

Marchetti posits that if a city grows in spatial extent while maintaining the population density of Hadrian’s Rome, then widespread automobile availability should enable cities of sizes of 50 million people, and a hypothetical means of transportation with a speed of 150 km/s should enable a city of a billion people. I will address the issue of transportation infrastructure and population density later, but for now I am skeptical that the assumption of constant population density is reasonable.

Marchetti speculates about possible future transportation technology, such as hypersonic flight or a maglev train in tube evacuated to near-vacuum conditions, a concept similar to the more recent Hyperloop (Musk (2013)). Such technologies could enable what Constantinos Doxiadis termed an ecumenopolis, or a planet-spanning city (Doxiadis (1962)).

What About Communications?

Already by 1994, the dawn of the World Wide Web, there was widespread recognition of the importance of emerging communication technologies. And yet, Marchetti, citing Grübler (1989), regarded transportation and communication technologies as synergistic, not substitutes, and thus was skeptical of the idea that telecommunication alone could be a world unifying principle.

Research since 1994 has largely vindicated Marchetti’s skepticism. Hong and Thakuriah (2018) find that smartphone usage increases travel overall. Choo, Lee, and Mokhtarian (2007) find that telecommunications have a mixed effect on overall travel but generally increases travel. Choo and Mokhtarian (2007), Mokhtarian (2008), and Mokhtarian (2009) all show that physical transportation and telecommunications are generally complements: if one increases, then the other increases. Lyons and Urry (2005) find that mobile device usage stimulates travel by allowing travel time to be more productive.

Clark and Unwin (1981) find that communications technology increases travel overall, though it decreases work travel in rural areas and especially increases social travel. Salomon (1985) and Salomon (1986) show that communications increases travel on net.

In contrast to the picture with communication technology in general, research shows that telecommuting can be a substitute for physical travel. Helminen and Ristimäki (2007) find that telecommuting reduces work travel. Kim (March 2016) annd Kim (June 2016) show that telecommuting increases non-work travel, as an example of the rebound effect, but decreases travel overall. Balepur, Varma, and Mokhtarian (1998) find the same thing. Choo, Mokhtarian, and Salomon (2005) and Henderson and Mokhtarian (1996) find that telecommuting decreases overall vehicle-miles traveled.

While modern communications technology changes the way we travel, and while we can imagine a world in which advanced telepresence is an adequate substitute for physical travel, there is little evidence that this is happening so far, and it is reasonable to suppose that physical transportation infrastructure will define the structure of cities for the foreseeable future.

Where are the Very Large Cities?

Marchetti considers not only the structure of individual cities, but also the relationships between cities. Zipf’s law (Zipf (1949)) is a well-known pattern whereby, when the populations of cities in a country are ranked, the nth value is proportional to 1/n. In other words, the second largest city has half the population of the largest city, the third largest city has a third the population of the largest city, and so on. Zipf’s law is a general pattern that has been observed in many domains besides city sizes.

Marchetti observes that there are few very large cities in the modern world, compared to what would be expected from Zipf’s law. To explain why, Marchetti observes that air travel creates corridors, often linear, such as Boston-New York-Washington, D.C. or Tokyo-Nagoya-Osaka. These corridors are too large geographically to function as unified labor markets for the general public, but fast air transportation integrates these cities economically for wealthy elites, which Marchetti suggests may be sufficient for these corridors to be functionally integrated. Marchetti then finds that when corridors are considered as functionally unified, Zipf’s law is found to much better fit world city size distribution.

Risks from Fast Transportation

The prospect of unifying world societies through fast transportation might not be perceived as an unalloyed good. Marchetti describes this as an ecological problem, by which he is referring not to environmental concerns but rather to a social cost of the loss of cultural diversity in the world, similar to how an environmental ecologist would wish to preserve species biodiversity.

Marchetti argues that people have the natural inclination to return to their “caves”, regardless of where the day’s business might take them. Therefore, fast transportation will allow low-friction transactions between people around the world, yet it should preserve a geographically-rooted sense of home and thus cultural diversity.

The Size of Empires

Cities, roughly defined as a 30 minute commute radius, are not the only structures based on travel that Marchetti considers. He observes that ancient empires showed a maximum of one month of travel from the periphery to the capital; where travel times were longer than that, peripheral regions tended to split into separate political units. The geographic size was then determined by whether the predominant mode of transportation was on foot or by horseback. The advent of steamships and railroads, and especially of aviation, has at least enabled from a transportation logistics standpoint a world-spanning empire. The one month limit may again be a constraint on the size of functional political units in a spacefaring future.

Conclusion

Marchetti (1994) describes the fundamental principle of commute travel time for understanding the size of cities. The paper has some limitations. I think he is off base with the constant density assumption to model cities with faster transportation infrastructure, and I do not think the discussion of the so-called ecological problem of high-speed transportation adequately addresses the issue. Still, the paper is valuable especially for integrating such a wide range of topics in a small amount of space, and doing so in a highly readable manner.

One implication of Marchetti’s work is that we should expect faster, cheaper, and safer transportation to manifest itself as more travel, rather than as saving time, money, and lives. This is not necessarily a bad thing, and it is an issue that is very familiar to people who understand the rebound effect in the context of energy markets. However, it calls into question the merit of strategies to address perceived negative impacts of transportation through better transportation infrastructure.

References

Marchetti, C. “Anthropological Invariants in Travel Behavior”. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 47(1), pp. 75-88. September 1994.

Zahavi, Y., The “UMOT” Project, Project No. DOT-RSPA-DPB, 2-79-3, U.S. Department of Transport, Washington, DC, 1979.

Zahavi, Y., Beckmann, M. J., Golob, T. F. The UMOT-Urban Interactions, Report No. DOT-RSPA-DPB-10/7, U.S. Department of Transport, Washington, DC, 1981.

Musk, E. “Hyperloop Alpha”. August 2013.

Doxiadis, C. A. “Ecumenopolis: Toward a Universal City”. Ekistics 13(75), pp. 3-18. January 1962.

Grübler, A., “The Rise and Fall of Infrastructures”, Thesis, Physica Verlag, Heidelberg, Germany, 1989.

Hong, J., Thakuriah, P. V. “Examining the relationship between different urbanization settings, smartphone use to access the Internet and trip frequencies”. Journal of Transport Geography 69, pp. 11-18. 2018.

Choo, S., Lee, T., Mokhtarian, P. L. “Do Transportation and Communications Tend to Be Substitutes, Complements, or Neither? U.S. Consumer Expenditures Perspective, 1984-2002”. Transportation Research Record Journal of the Transportation Research Board 1, pp. 121-132. 2007.

Choo, S., Mokhtarian, P. “Telecommunications and travel demand and supply: Aggregate structural equation models for the US”. Transportation Research Part A-Policy and Practice, 41(1), pp. 4-18. January 2007.

Mokhtarian, P. “Telecommunications and Travel: The Case for Complementarity”. Journal of Industrial Ecology 6(2), pp. 43-57. February 2008.

Mokhtarian, P. “If telecommunication is such a good substitute for travel, why does congestion continue to get worse?”. The International Journal of Transportation Research 1(1), pp. 1-17. 2009.

Lyons, G., Urry, J. “Travel time use in the information age”. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 39(2-3), pp. 257-276. February-March 2005.

Clark, D., Unwin, K. I. “Telecommunications and travel: Potential impact in rural areas”. Regional Studies 15(1). February 1981.

Salomon, I. “Telecommunications and Travel: Substitution or Modified Mobility?”. Journal of Transport Economics and Policy 19(3), pp. 219-235. September 1985.

Salomon, I. “Telecommunications and Travel: Substitution or Modified Mobility?”. Journal of Transport Economics and Policy 19(3), pp. 219-235. September 1985.

Salomon, I. “Telecommunications and travel relationships: a review”. Transportation Research Part A: General 20(3), pp. 223-238. May 1986.

Helminen, V., Ristimäki, M. “Relationships between commuting distance, frequency and telework in Finland”. Journal of Transport Geography 15(5), pp. 331-342. September 2007.

Kim, S. “Two traditional questions on the relationships between telecommuting, job and residential location, and household travel: revisited using a path analysis”. The Annals of Regional Science 56(2), pp. 537-563. March 2016.

Kim, S. “Is telecommuting sustainable? An alternative approach to estimating the impact of home-based telecommuting on household travel”. International Journal of Sustainable Transportation 11(2), pp. 72-85. June 2016.

Balepur, P. N., Varma, K. V., Mokhtarian, P. L. “Transportation impacts of center-based telecommuting: Interim findings from the Neighborhood Telecenters Project”. Transportation 25, pp. 287-306. August 1998.

Choo, S., Mokhtarian, P. L., Salomon, I. “Does telecommuting reduce vehicle-miles traveled? An aggregate time series analysis for the U.S.”. Transportation 32, pp. 37-64. 2005.

Henderson, D. K., Mokhtarian, P. L. “Impacts of center-based telecommuting on travel and emissions: Analysis of the Puget Sound Demonstration Project”. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment 1(1), pp. 29-45. September 1996.

Zipf, George K. “Human behavior and the principle of least effort”. Cambridge, (Mass.): Addison-Wesley, 1949, pp. 573.