Characteristics of a city, including its size, have a qualitative effect on how people live.

City Size and Walking Speed

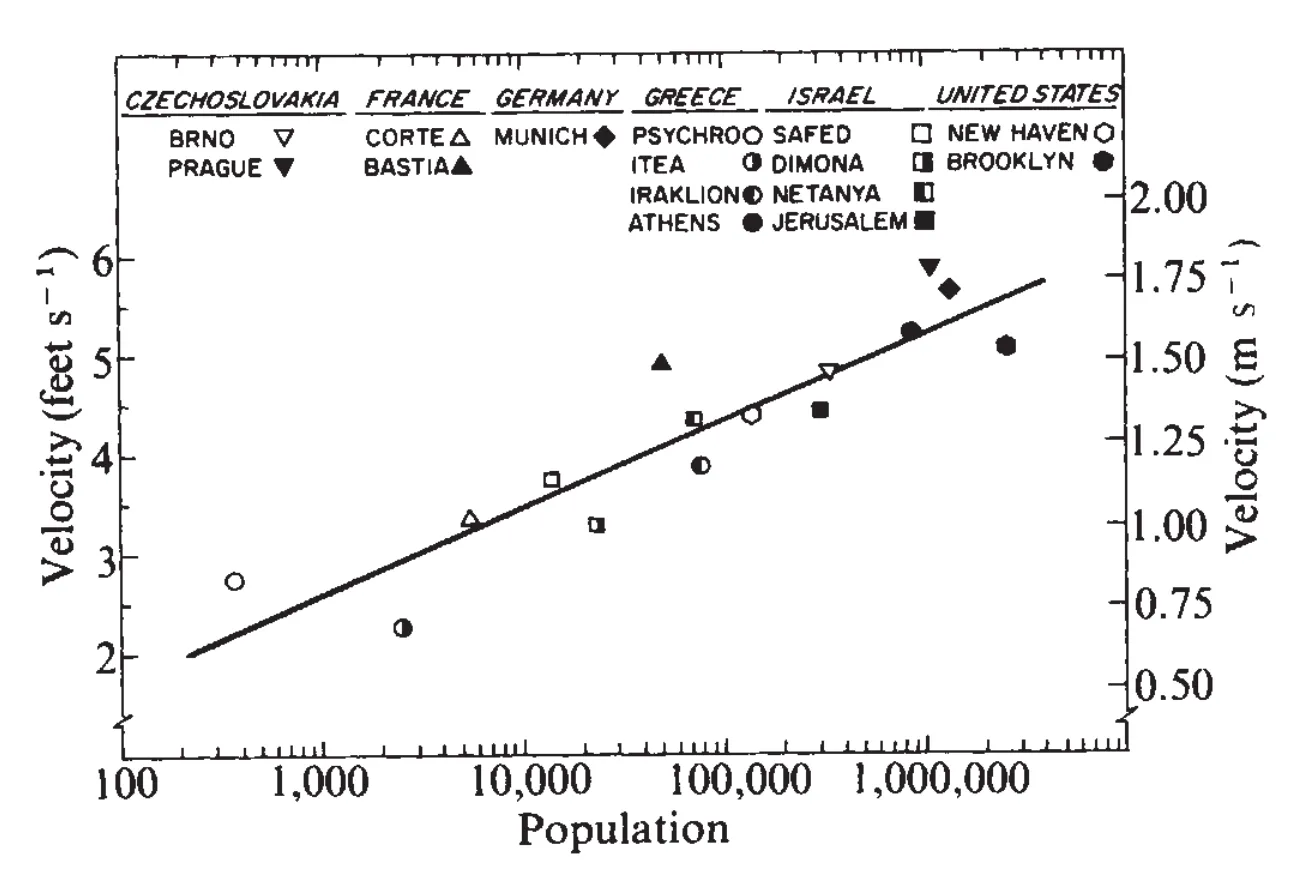

Much research has established a relationship between city size and walking speed, whereby people tend to walk faster in larger cities. The earliest well-known such study is Bornstein and Bornstein (1976), which finds the following relationship between average walking speed and the logarithm of city size.

Walking Speed and City Size as measured by Bornstein and Bornstein (1976).

Walking Speed and City Size as measured by Bornstein and Bornstein (1976).

Bornstein and Bornstein (1976) use a simple methodology. They went to 15 cities around the world and directly measured walking speed. They then performed a regression between city size and walking speed to produce the above chart. The relationship is significant at p=0.001, a strong relationship.

Reflecting its time, Bornstein and Bornstein (1976) expresses anxiety about population growth. The opening sentence is,

THE specific effects of population pressure on the quality of everyday life should be of pressing social and policy concern; and although population studies have proliferated in the behavioural sciences, research has focused primarily on fertility-related behaviours.

Citing Fawcett (1973), their interpretation of the result is that high walking speed is an adaptation to the stress of crowding in large cities. However, there is nothing in the data that suggests that this is the correct interpretation.

Wirtz and Ries (1992) dispute the findings of Bornstein and Bornstein (1976), arguing that these authors made the mistake of failing to control for demographic factors. Larger cities tend to have disproportionate populations of young people without families, who typically walk faster. Wirtz and Ries (1992) argue that when demographics are controlled for, the city size-walking speed link disappears. Wirtz and Ries (1992) use the same methodology on 14 cities in Europe that Bornstein and Bornstein (1976) use. The only major difference between the two papers is that Wirtz and Ries (1992) interpret the results differently: higher walking speed in large cities is due to a different demographic composition rather than the psychological pressures of density.

Moving away of walking speed based entirely on city size, let us consider Schmitt and Atzwanger (1995). They measure walking speed and interviewed some people to find out their socioeconomic status (SES), which is defined as a composite measure of prestige of occupation, income, and education. They find a statistically significant correlation between SES and walking speed for men but not for women (though women have a weak correlation). The authors’ explanation is rooted in sociobiology: since men have to compete for mates and not vice versa, men with higher status are more compelled to signal status by walking more quickly.

Next, let us consider Levine and Norenzayan (1999), who introduce several more innovations into the discussion. Following some earlier authors, they broaden the question of walking speed into “pace of life”, which is represented by three metrics: walking speed, work speed for postal clerks, and accuracy of bank clocks. These metrics correlate well with each other (Levine and Barlett 1984) and, as Levine and Norenzayan (1999) suggest, serve as a good proxy for pace of life. Concerned about the unsystematic manner in which cities are chosen for most previous studies, Levine and Norenzayan (1999) choose the largest cities in 31 countries for comparison. They furthermore consider several city features that might predict pace of life: gross domestic product, climate (hot or cold), individualistic vs. collectivist cultures, and city size. Most of these metrics are derived from standard sources, with the individualism/collectivism metric based on the measurements of Diener, Diener, and Diener (1995). The three metrics for pace of life are derived from readily available observations and are aggregated into a single metric.

Levine and Norenzayan (1999) find, as hypothesized, that pace of life correlates with GDP, with colder climates, and with more individualistic cultures. The authors also tackle questions related to well-being. The authors find that there is a statistically significant correlation between pace of life and coronary heart disease, which is understood to be influenced by chronic stress. They also find that smoking rates correlate with pace of life, and they posit that smoking is a response to the stress induced by pace of life.

It may be surprising, then, that according to Levine and Norenzayan (1999), subjective well-being (SWB) also positively correlates with pace of life. Here, SWB is derived from Veenhoven (1993), which determines SWB from surveys of how happy people are. The interpretation of Levine and Norenzayan (1999) is that SWB correlates with GDP (see Diener, Diener, and Diener 1995), and this effect is more important than the negative impacts of smoking and heart disease.

Finnis and Walton (2008) reject the idea that walking speed is in fact an indicator of pace of life, and they discuss walking speed in terms of the built environment. They measure average speed in several locations in New Zealand. They find some obvious things, like walking speed tends to be slower for pedestrians with baggage and depends on the type of shoes and the slope of the terrain. They find that, once the more obvious factors are considered, that there is actually a slight negative correlation between city size and walking speed. Unfortunately, the paper does not deliver on its promise of analyzing how build environment characteristics influence walking speed, but given constraints such as Marchetti’s constant, they argue that a high walking speed helps promote car-free environments.

Franěk (2012) considers the impact of two built environment metrics—the presence of vegetation and the busyness of roads—on walking speed, and he finds that walking speed tends to be higher when vegetation is lacking and when roads are more busy. His interpretation is that busy roads and a lack of vegetation create stress for pedestrians and induce them to walk more quickly.

Shen and Yen (2025) conduct a meta-analysis of walking speed studies, each of which analyzes walking speed in terms of several variables (though not every study uses every variable). They then cluster the results using DBSCAN, a popular clustering algorithm in unsupervised machine learning. They find three clusters with a handful of outlier points. They find the demographic composition of a city and the weather to be highly significant factors, neither of which should be a surprise.

City Size and Communication

The kind of city we live in shapes how we communicate. In a broader review of how socioeconomic properties vary with size, Bettencourt (2013) suggests, based on theory, that the volume of cell phone calls should vary with the 7/6 power of city population. That is to say, is the city size grows by 1%, when the call volume should grow by about 1.67%. This question was invested empirically by Schläpfer et al. (2014). They study cell phone call volume in Portugal and landline call volume in the United Kingdom, and they measure these quantities in terms of city size. In both cases, they find a scaling exponent of 1.10, which is significantly greater than 1 but less than the 7/6 predicted theoretically by Bettencourt (2013).

Sapienza et al. (2023), for instance, consider a data set of about 500,000 cell phone calls across 22 countries. They find, as do many other researchers, that urban dwellers spend more time on their phones than rural dwellers: a daily average of 175 minutes versus 152 minutes. However, the others obsever that this difference may be explained by the preferences of people who live in the cities, as opposed to an effect caused by the city itself. Controlling for demographics, Sapienza et al. (2023) find that people who live in urban areas spend 5.12% more time on their cell phones than their rural counterparts, a smaller but still highly significant difference.

To consider the self-selection question–that perhaps people who use their cell phones more gravitate toward cities, rather than cities being the cause of phone usage–Sapienza et al. (2023) the study the patterns of phone usage of people who move. Several months after a rural-to-rural or an urban-to-urban move, phone usage decreases by about 6% below the baseline. For urban-to-rural moves, the decrease is 15%, while for a rural-to-urban move, phone usage increases by 12%. These figures suggest that the living environment itself, and not just selection effects, explain phone usage.

References

Sapienza, A., Lítlá, M., Lehmann, S., Alessandretti, L. “Exposure to urban and rural contexts shapes smartphone usage behavior”. PNAS Nexus 2(11): pgad357. November 2023.

Bornstein, M. H., Bornstein, H. G. “The pace of life”. Nature 259, pp. 557-559. February 1976.

Fawcett, J. T. (ed.) Psychological perspectives on population. ISBN: 0-465-06673-9. 1973.

Wirtz, P., Ries, G. “The Pace of Life - Reanalysed: Why Does Walking Speed of Pedestrians Correlate With City Size?”. Behavior 123(1-2), pp. 77-83. January 1992.

Schmitt, A., Atzwanger, K. “Walking fast-ranking high: A sociobiological perspective on pace”. Ethology and Sociobiology 16(5), pp. 451-462. September 1995.

Levine, R.V., Norenzayan, A. “The pace of life in 31 countries”. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 30(2), pp. 178-205. March 1999.

Levine, R.V., Bartlett, K. “Pace of Life, Punctuality, and Coronary Heart Disease in Six Countries”. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 15(2), pp. 233-255. June 1984.

Diener, E., Diener, M., Diener, C. “Factors predicting the subjective well-being of nations”. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 69(5), pp. 851-864. November 1995.

Veenhoven, R. “Happiness in Nations”. World Database of Happiness. 1993.

Finnis, K.K., Walton, D. “Field observations to determine the influence of population size, location and individual factors on pedestrian walking speeds”. Ergonomics 51(6), pp. 827-842. June 2008.

Franěk, M.A. “The effect of urban vegetation and traffic intensity on walking speed”. In Urban Planning and Transportation (UPT 12): Proceedings of the 5th WSEAS International Conference 2012 (pp. 163-166). Cambridge: Athens. 2012.

Shen, W.T., Yen, B.T. “Critical factors influenced pedestrian walking speed: A meta-analysis”. Research in Transportation Economics 111: 101564. June 2025.

Bettencourt, L. “The Origins of Scaling in Cities”. Science 340(6139), pp. 1438-1441. June 2013.

Schläpfer, M., Bettencourt, L., Grauwin, S., Raschke, M., Claxton, R., Smoreda, Z., West, G.B., Ratti, C. “The scaling of human interactions with city size”. Journal of the Royal Society Interface 11(98). September 2014.