A growing societal scale–rising population and increasing technological prowess–raises the question of what severe risks that scale may pose.

Understanding Existential Risk

Bostrom (2013) defines existential risk as follows.

An existential risk is one that threatens the premature extinction of Earth-originating intelligent life or the permanent and drastic destruction of its potential for desirable future development.

Bostrom (2013) further delineates four classes of existential risk.

- Human extinction, the most familiar kind of existential risk, is defined more broadly as the extinction of all life on Earth that is intelligent or has the potential to evolve intelligence, thus foreclosing the possibility of a technological civilization against arising on Earth.

- Permanent stagnation is a scenario in which human civilization, though long-lasting, is unable to advance beyond a technological level that is far below the theoretical limit.

- Flawed realization is a scenario in which human civilization attains a state of technological maturity but in a way that is irredeemably flawed. The definition of “flawed” is necessarily subjective.

- Subsequent ruination is a scenario in which human civilization achieves technological maturity, but the state of maturity is prematurely and permanently ruined.

A global catastrophic risk, as defined for example by Currie and hÉigeartaigh (2018), is a risk that has the potential to cause serious harm on a planetary scale. Bostrom (2013) argues that, serious though a global catastrophic risk would be, an existential risk is far worse because it would foreclose a potential future that is far vaster than the society that exists today. The argument for this claim is based on utilitarian ethics and two premises. The first is an aggregative view of wellbeing: if two similar people enjoy a similar high standard of being, then this should be twice as good as a single person enjoying the high standard of being. The second premise is that one should not discount the future for the sake of utilitarian calculus: all else equal, the happiness of a person in the far future is morally equivalent to the happiness of a person today.

Given the extreme gain in utility that would come with attaining a positive and lasting technological maturity, Bostrom (2013) finds that reducing existential risk is a overriding priority for allocation of scarce altruistic effort. Bostrom consider other ethical frameworks besides utilitarianism, and while an argument for the importance of avoiding existential risk can be made in other frameworks, it is not clear that these other frameworks imply that existential risk reduction is an overriding priority as it is under utilitarianism. Within utilitarianism, the first premise discussed above in particular is contested by averagism in population ethics. As Greaves (2017) explains, averagism in an ethical framework that regards the average wellbeing of a population as the most morally relevant quantity. This contrasts to totalism, which holds that the sum of wellbeing across a population is more morally relevant.

Although the paper does not use the term, Bostrom (2013) invokes two variants of the precautionary principle. The first is that, due to the extreme harm that could result from existential risk, it is better to presume that a thing is risky when faced with uncertainty. Bostrom treats the harm of existential risk as effectively infinite, thus presenting the calculus for existential risk reduction as a form of what Leben (2020) characterizes as Pascal’s Wager. Bostrom (2013) does not address the question of whether specific proposed actions to reduce existential risk do in fact reduce risk, or iff such actions may be motivated by malign motives, though he does note this risk exists due to imperfect institutions. The second variant of the principle is normative uncertainty, which holds that contested moral vales, such as biodiversity protection, should be respected when there is not great cost to doing so. Bostrom argues from normative uncertainty that it is morally good for humanity to keep options open into the future, which entails pursuing technological maturity.

Classifying Risk

Bostrom (2013) argues that the most serious existential risks in the coming centuries are the result of human activity. Natural risks, such as an asteroid impact, a supervolcano eruption, or a gamma ray burst, have not killed all of humanity over hundreds of thousands of years (though as Noerwidi (2012) recounts, the Toba eruption of 74,000 years ago came close), and so they are unlikely to do so in the next few centuries.

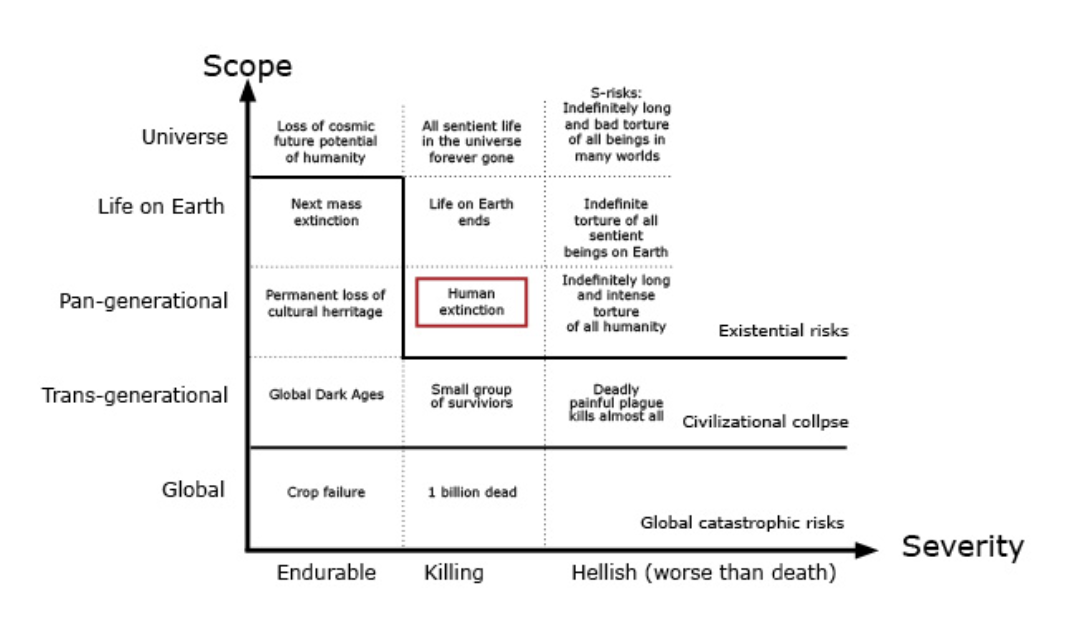

Turchin and Denkenberger (2018) portray a two-dimensional classification of risk by scope and severity.

Classification of existential risk by scope and severity. Image from Turchin and Denkenberger (2018), adapted from Bostrom (2003).

Classification of existential risk by scope and severity. Image from Turchin and Denkenberger (2018), adapted from Bostrom (2003).

Here, a global catastrophic risk would kill at least a billion people, and though not necessary an existential risk on its own, could lead to other events that do constitute existential risk. A trans-generational event is a civilization collapse that lasts for multiple generations but is not permanent. A pan-generational event here is taken strictly as human extinction, and it excludes permanent civilization collapse that nonetheless admits survivors. Not pictured above, but described in the text, is what Daniel (2017) calls S-risks: risks of suffering on a cosmic scale.

For ease of communication, Turchin and Denkenberger (2018) propose coding with six colors.

| Color | Proposed Action | Example Risks |

|---|---|---|

| White | Do Nothing | Sun becomes a red giant, natural false vacuum decay |

| Green | Observation, minor tax incentives and deployment | Asteroid impact, particle accelerator disaster |

| Yellow | Major programs and investments | Supervolcano, global warming, natural pandemic |

| Orange | Manhattan Project-scale program | Nanotech catastrophe, synthetic biology catastrophe, nuclear war, agricultural yield shortfall |

| Red | Major command and control regulations | Misaligned artificial intelligence |

| Purple | War footing | An existential risk poses an imminent danger |

Will Risk Peak and Decline?

One may fear that existential risk will accumulate with technological development, making an eventual existential catastrophe inevitable. However, Trammell and Aschenbrenner (2024) construct a model to suggest that existential risk may peak and decline over time, perhaps to zero in such a way that the probability of civilizational survival over the long-term is positive.

Trammell and Aschenbrenner (2024), following the terminology of previous authors, distinguish between state risks and transition risks. A state risk is one which applies for each unit of time at a fixed technological level. A transition risk is one posed by the invention of a new technology, and it disappears after the technology is established. They construct a model for the case in which only state risks apply, and one for the case in which which both state and transition risks apply.

First, Trammell and Aschenbrenner (2024) consider state risk only with no policy for risk reduction. They show that, contrary to the intuition of some, an acceleration of the development of technology generally reduces long-term risk, though it may induce short-term risk and lower civilization’s life expectancy. The intuition behind their result is that the total long-term risk can be calculated as the integral over all time of the risk at any given moment. An acceleration of technology–whether one-time or permanent–compresses the points in the x-axis of the curve and thus reduces the area under it. They show that a permanent acceleration of technology might even convert a civilization from one that is doomed to have an eventual existential catastrophe to one that has a chance of surviving in the long term. These results require that the level of state risk for a technology level converges to zero as the level approaches infinite.

Next, Trammell and Aschenbrenner (2024) consider state risk with a deliberate policy of risk reduction. In their model, it is possible that a certain portion of resources that would otherwise to go consumption are instead spent on risk reduction. In this case, risk grows endlessly with advancing technology in the absense of any mitigation. The risk level has constant elasticity–that it, it varies with a fixed percentage–with respect to both the technology level and the mitigation spending. If the latter elasticity is greater than the former elasticity, then it is possible to invest greater amounts of spending in safety over time while maintaining a positive probability of forever avoiding existential catastrophe. Otherwise, it is impossible.

Finally, Trammell and Aschenbrenner (2024) broaden the model to include transition risk as well as state risk. With this, they find that it is necessary for the elasticity with respect to risk mitigation spending to exceed the sum of the elasticities with respect to state risk resulting from advancing technology and the transition risk at a given time. Though this condition is more stringent, a result holds in all cases that a technology acceleration improves the likelihood of the civilization’s long-term survival, and it may even grant a chance of long-term survival to a civilization that would otherwise have none.

Trammell and Aschenbrenner (2024) observe that, in a civilization that achieves long-term survival, existential risk must converge to zero, which implies that there is a peak and decline. They analogize this phenomenon to the environmental Kuznets curves of Stokey (1998), which posits that wealthier societies are willing to spend more on mitigation of environmental problems, which leads to an observed peak and decline in many environmental impacts. Trammell and Aschenbrenner (2024) does have some limitations. It treats technological development as monolithic, and it does not address the possibility that which technologies are developed at a particular time can be subject to policy. The models are also very theoretical in nature rather than empirical.

References

Bostrom, N. “Existential Risk Prevention as Global Priority”. Global Policy 4(1), pp. 15-31. March 2013.

Currie A, hÉigeartaigh, S. Ó. “Working together to face humanity’s greatest threats: Introduction to the future of research on catastrophic and existential risk”. Futures 102, pp. 1-5. September 2018.

Greaves, H. “Population axiology”. Philosophy Compass 12(11): e12442. November 2017.

Leben, D. “Pascal’s Artificial Intelligence Wager”. Philosophy Now. 2020.

Turchin, A., Denkenberger, D. “Global Catastrophic and Existential Risks Communication Scale”. Futures 102, pp. 27-38. September 2018.

Noerwidi, S. “Younger Toba Tephra 74 Kya: Impact On Regional Climate, Terrestial Ecosystem, And Prehistoric Human Population”. AMERTA 30(1). 2012.

Bostrom, N. “Astronomical Waste: The Opportunity Cost of Delayed Technological Development”. Utilitas 15(3), pp. 308-314. November 2003.

Daniel, M. “S-risks: Why they are the worst existential risks, and how to prevent them”. EAG Boston 2017. June 2017.

Trammell, P., Aschenbrenner, L. “Existential Risk and Growth”. Global Priorities Institute Working Paper No. 13-2024. December 2024.

Stokey, N. L. “Are There Limits to Growth?”. International Economic Review 39(1), pp. 1-13. February 1998.