This article is Version 2. Version 1 can be found here.

As we discuss scaling in human societies, the question naturally arises of what factors will eventually limit growth.

Malthusianism

One of the earliest famous works on ecological limits to growth is the 1798 essay of Thomas Malthus, An Essay on the Principle of Population (Malthus (1798)). In the introduction, Malthus states the basic predicament.

Population, when unchecked, increases in a geometrical ratio. Subsistence increases only in an arithmetical ratio. A slight acquaintance with numbers will shew the immensity of the first power in comparison of the second.

“Geometrical” refers to a sequence where each term is a fixed multiple of the previous term, while “arithmetical” refers to a sequence in which each term is a fixed quantity added to the previous term. A geometric sequence is also an exponential sequence. It can easily be shown that, with the multiplicative ratio is greater than 1–i.e. if population growth is above the replacement rate–then the ratio between the geometric and arithmetic sequences will become arbitrarily large. Thus under Malthus’ scenario, the food availability per person must decrease to the point that pushes humanity to a subsistence level, after which further population growth is impossible.

Malthus argues that, absent constraints, birth rates should exceed death rates and by a constant amount, giving rise to geometric growth. It is not clear how Malthus concludes that arithmetic growth in the food supply is to be expected, and this hypothesis may have been offered for the sake of pedagogy; Malthus’ argument works if any growth in the food supply that is less than exponential is assumed.

Malthus sees two constraints to growth: “misery and vice”. Misery can be regarded as a Malthusian catastrophe in the sense that is generally understood today, with famine, disease, and war the expected culprits. Malthus regards marriage at a young age and building a family to be the normative lifestyle, and vice to be a deviation from this lifestyle. Thus Malthus might look at the contemporary phenomenon of subreplacement birth rates in much of the world and regard them as vindication of his model.

Perhaps most surprisingly to modern readers, Malthus does not mention, let alone advocate, population control as a solution to population growth, and he offers no policy prescriptions beyond scaling back the Poor Laws, which Malthus believes contribute to the birth rate and thus do nothing to alleviate poverty overall. Indeed, toward the end of the essay, Malthus describes population pressure dynamics as “providential” and as the source of the hardship that is necessary for spiritual growth.

Limits to Growth

The Limits to Growth (Meadows et al. (1972)) is the title of a famous 1972 report based on the World3 computer model of the Club of Rome. The model simulates the development and interplay of five factors: human population, food production, industrialization, pollution, and nonrenewable resource consumption.

Meadows et al. is well-known as one of the major early studies in computational ecology. However, the report has also gained notoriety for pessimistic and inaccurate forecasts. For example, Meadows et al. projected the expected lifetime of various nonrenewable resources, including metals and fossil fuels. The projections are based on three scenarios: a simple ratio of known, economic reserves to annual production (the R/P ratio), the R/P ratio with a projected annual growth rate in the usage of the resources, and the R/P ratio with projected annual growth rate with reserves multiplied by five. Many resources, including petroleum and natural gas, should have run out by 2024 under all three scenarios.

Meadows et al. is pessimistic about the capacity of new technology to address limits to growth. In their discussion of the subject, Meadows et al. address three barriers for technology to achieve sustainability. First, new technology must overcome the limitations on resource availability discussed above. Second, technology must control rising pollution, which the World3 model holds will threaten human civilization. Third, technology must increase yields in food production to feed a rising human population.

Several updates and analyses of The Limits to Growth have been published since 1972, including Herrington (2021). She finds that, relative to the most of the scenarios of The Limits to Growth, the world has shows greater reserves of non-renewable resources, most aligning with that paper’s “Business As Usual - 2” (BAU2) scenario. Considering a range of ecological metrics, she finds that BAU2 and CT–the Comprehensive Technology scenario which posits a higher than historical rate for technologies for pollution control, resource efficiency, and agricultural yields–best fit empirical data. Both scenarios posit a peak in world gross domestic product by the mid-21st century, though the decline from the peak is sharper under BAU2. Herrington posits that pollution, particularly greenhouse gas emissions and the resulting climate change, is the most immediate cause of collapse under BAU2.

Herrington (2021) suffers from a similar problem as the original The Limits to Growth and other similar studies in that it applies a limited role to new technology, despite technology being the major reason for deviation between the forecasts of The Limits to Growth and reality. She forecasts that under the CT scenario, the rate of technological improvement–necessary to extend resource availability, food production, and pollution control–will stagnate.

Fossil Fuel Depletion

“Peak oil” refers to an expected worldwide peak, followed by decline, in world oil production.

Hubbert Peak

Peak oil forecasts draw heavily on the Hubbert peak, developed by the petroleum geologist M. King Huubert (Hubbert (1956)). Hubbert observed that fossil fuel production in a region, such as a state in the United States, tends to follow a normal curve, or a bell-shaped curve. Such a curve initially appears to be exponential, showing a certain percentage increase every year, but eventually shows a slowing growth rate, a peak, and then a decline.

Hubbert applied a best fit normal curve to oil and gas production in the United States and forecast that these two commodities should see peak production around, respectively, 1965 and 1975. According to Kriel (2024), the United States saw a peak in oil production in 1970 of 9.6 million barrels per day (mb/d) and a general decline to 5.0 mb/d in 2008, but then oil production rebounded with the deployment of hydraulic facturing and horizontal drilling, reaching a value of 12.9 mb/d in 2023.

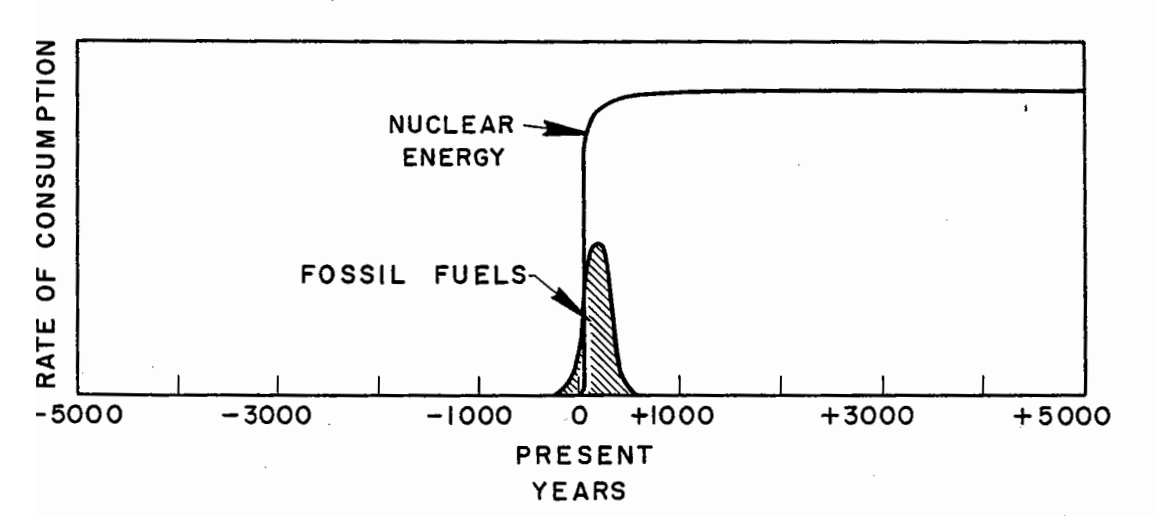

A lesser-known aspect of Hubbert (1956) is the advocacy for nuclear power. Written at the dawn of the civilian nuclear industry, and at a time of great expectations for it, Hubbert observes that the energy content of then-known uranium reserves vastly exceeded that of fossil fuel reserves, and with population stabilization in the near future, nuclear power had the potential to power civilization at a high standard of living for millennia.

Potential Production of Fossil Fuels and Nuclear Power. Image from Hubbert (1956).

Potential Production of Fossil Fuels and Nuclear Power. Image from Hubbert (1956).

Hubbert’s forecast for United States oil production appeared to be fairly accurate for 50 years after the paper’s publication, but he too failed to foresee the eventual impact of oil production technology from the late 2000s. So far, he has also greatly overestimated the potential of nuclear power, but based on a 5000 year forecast window, the industry’s slow start in the first 70 years might be only a blip.

As Priest (2014) recounts, defenders of the Hubbert peak hypothesis often argue that the model applies to conventional oil and not to deepwater oil or oil obtained from shale, thus abstracting away a principle objection to the Hubbert peak model that it does not account for the role of new technology and price signals.

Peak Oil

The modern peak oil movement began with the short editorial Campbell and Laherrère (1998), which forecast a world peak oil production no later than 2010. The forecast is based on a simple feature of the bell-shaped curve posited by Hubbert (1956): it is symmetric around the peak value, and thus the peak value occurs when cumulative production is half of total eventual production. Campbell and Laherrère estimate the former at 850 billion barrels of oil, and they estimate the latter at 850 billion barrels of proven reserves and 150 billion barrels of reserves that were yet to be discovered. In assessing reserves, Campbell and Laherrère allege that oil companies and national governments of oil-producing nations have systematically inflated their reserve estimates, justifying smaller reserve estimates than most published values at the time.

Hubbert Linearization

Building from earlier work, in 1982 Hubbert introduced Hubbert linearization (Hubbert (1982)), a mathematical technique for estimating ultimate reserves of a resource. It can be shown that a, when annual oil production follows a normal distribution function as posited in Hubbert (1956), the percentage growth rate of production, which is the derivative of annual production, divided by annual production, is a linear function with negative slope. The relationship between annual production Q(t) and the growth rate P(t) is also linear. When they are plotted on a single graph, Hubbert showed that the intersection with the Q axis is the ultimate recoverable reserve.

Rutledge (2011) applies a variant to Hubbert linearization to world coal production. He uses a logistic and a cumulative normal model, linearized respectively by logit and probit transformations, with the particular model for each region chosen by whichever yields a higher correlation coefficient. The model is then applied to 14 world regions, as coal is not widely traded worldwide, and the values from the regions are summed to attain an estimate of remaining world coal reserves. The estimate is a total of 680 billion tons of world production, past and future. This estimate is a bit more than half of the World Energy Council’s estimate and a fifth of those of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Rutledge distinguises between “reserves”, which are known coal deposits that can be recovered today economically, and “resources”, which are not reserves but may become reserves under plausible economic conditions. Thus Rutledge does not foresee that absolute resource constraints will limit coal production, but rather economic conditions.

Internal Limits to Growth

Manfroni et al. (2013) situate their work in the context of limits to growth, but while most works in this genre focus on external limits–resource availability and pollution–this paper focuses on internal limits to growth, specifically on working hours.

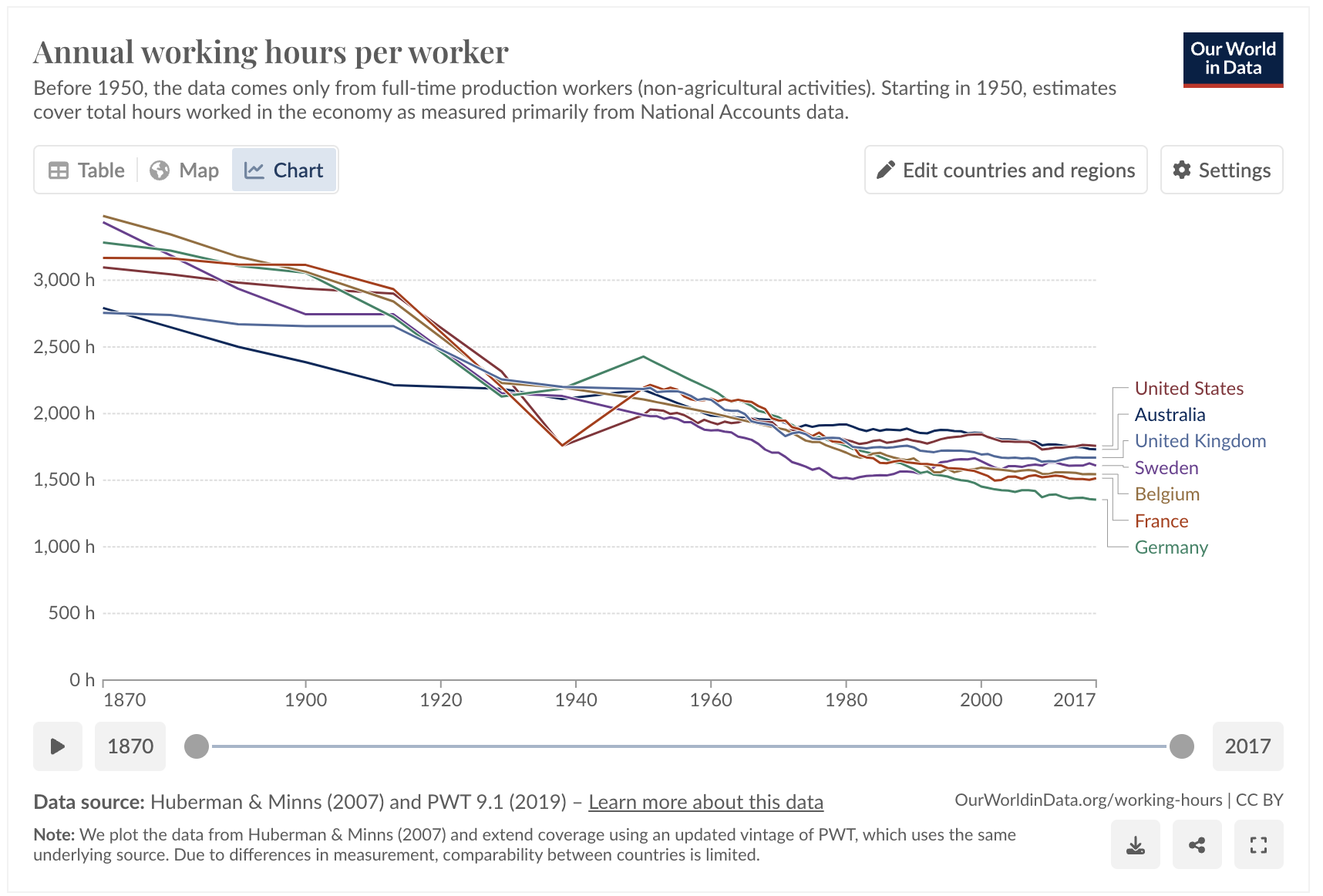

Our World in Data documents that, in several wealthy countries, average working hours have generally fallen since the 19th century.

Working hours in select countries from 1870 to 2017. Image from Our World in Data.

Working hours in select countries from 1870 to 2017. Image from Our World in Data.

Manfroni et al. cite Zipf (1941), who, working in the wake of the Great Depression, identifies the saturation of consumptive capacity as the operating limit to growth during that time. For economies to continue to grow, it is necessary for individuals to consume more, which in turns necessitates a greater amount of leisure time and thus fewer working hours.

Therein lies a paradox, according to Manfroni et al. Economic models, such as those based on the Solow-Swan growth model (see Solow (1956) and Swan (1956)), assign a prominent role to labor in economic growth. Thus according to Manfroni et al., more leisure is necessary to sustain the consumptive driver of growth, but this necessarily comes at the expense of working hours, which are necessary to sustain the productive driver of growth. This paradox is what Manfroni et al. identify as an internal limit to growth.

Manfroni et al. offers important insight about the role of working hours in economic growth, and its hypothesis serves as a plausible explanation for why economic growth has been slowing in many wealthy countries since the early 1970s, as documented by Cowen (2011). However, the work suffers from several significant shortcomings. The treatment of consumption as a driver of economic growth is superficial and does not engage with recent economic research on the subject. Like many Malthusian works, Manfroni et al. does not sufficiently account for the role of new technology. In particular, it does not assess the potential for technology to sustain economic growth despite a decline in working hours, even though this has been the case in the past.

References

Malthus, T. R. An Essay on the Principle of Population. 1798.

Manfroni, M., Velasco-Fernández, R., Pérez-Sánchez, L., Bukkens, S.G., Giampietro, M. “The profile of time allocation in the metabolic pattern of society: An internal biophysical limit to economic growth”. Ecological Economics 190: 107183. December 2021.

Zipf, G.K. “National unity and disunity; the nation as a bio-social organism”. Principia Press. 1941.

Solow, R.M. “A contribution to the theory of economic growth”. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 70(1), pp. 65-94. February 1956.

Swan, T.W. “Economic Growth and Capital Accumulation”. Economic Record 32(2), pp. 334-361. November 1956.

Cowen, T. The Great Stagnation: How America Ate All The Low-Hanging Fruit of Modern History, Got Sick, and Will (Eventually) Feel Better. Dutton. January 2011.

Meadows, D. H., Meadows, D. L., Randers, J., Behrens, W. The Limits to Growth. The Club of Rome. 1972.

Herrington, G. “Update to limits to growth: Comparing the World3 model with empirical data”. Journal of Industrial Ecology 25(3), pp. 614-626. June 2021.

Hubbert, M. K. “Nuclear Energy and the Fossil Fuels”. Houston, TX: Shell Development Company, Exploration and Production Research Division. March 1956.

Kriel, E. “United States produces more crude oil than any country, ever”. United States Energy Information Administration. March 2024.

Priest, T. “Hubbert’s Peak: The Great Debate over the End of Oil”. Historical Studies in the Natural Sciences 44(1), pp. 37-79. February 2014.

Campbell, C.J., Laherrère, J.H. “The end of cheap oil”. Scientific American 278(3), pp. 78-83. March 1998.

Rutledge, D. “Estimating long-term world coal production with logit and probit transforms”. International Journal of Coal Geology 85(1), pp. 23-33. January 2011.

Hubbert, M. K. “Techniques of Prediction as Applied to the Production of Oil and Gas”. 1982.